Background

Background

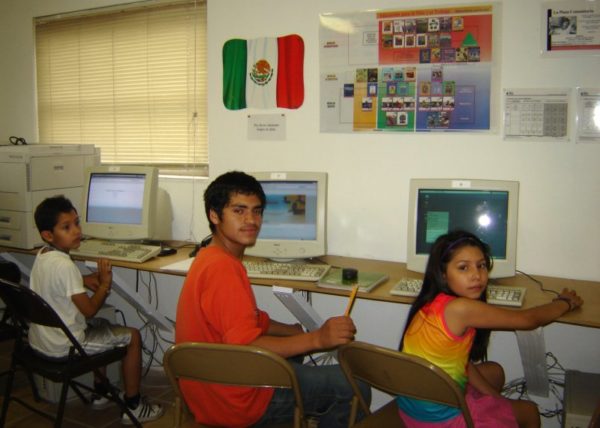

Farm workers and their families face a unique set of challenges in getting an education. Many farm workers have completed relatively few years of formal schooling, according to the most recent National Agricultural Workers Survey. The average level of formal education completed by farm workers is ninth grade. Additionally, only ten percent of migrant farm workers finish high school. This is partially due to the lack of educational opportunities in their countries of origin.

Obstacles to Education

Once they come to the U.S., the primary obstacle standing between adult farm workers and formal education is work. Farm workers are paid sub-poverty wages to perform long hours of backbreaking labor. Their priority may be survival rather than going to school. However, even if they did have the time, energy, and financial resources to go to school, educational institutions are usually located far away from farm worker communities, and affordable transportation is limited (not to mention undocumented workers are prohibited from holding a driver’s license in most states).

Another significant obstacle to education is cultural barriers, including language barriers. Literacy programs in farm workers’ primary language may be difficult to come by. According to the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS), 62 percent of farm workers’ primary language is Spanish, while 98 percent had the ability to speak Spanish (regardless of their ability to speak English). 34 percent of farm workers speak English “somewhat” or “well”. NAWS finds “The highest grade completed varied by place of birth. On average, the highest grade completed by workers born in the United States was 12th, and the highest grade completed by workers born in Mexico or other countries was 7th. Most U.S.-born farmworkers completed the 12th grade or higher (75%) as did 14 percent of Mexico-born workers.”

In terms of higher education, again, for students living in rural areas, the nearest educational institution can be far away, with no easily accessible transportation. The cultural differences can be overwhelming as well to go from smaller areas to bigger towns.

Furthermore, undocumented students who want to go to college may have to pay out of state or even international student tuition instead of in-state tuition. In the past decade, only 25 states have passed laws allowing in-state tuition for undocumented immigrants, and some of them do not allow for financial aid. Most often undocumented students will be forced to go to private universities who offer aid or not attend college at all. Even if students decide to attend college, most laws prohibit undocumented students from working within the school or paid internships that could potentially help them with daily finances, graduation requirements, or paying for their education . There are estimated 400,000 undocumented students at post-secondary institutions currently. Even if people attain the education to get licensed in their profession, the majority of states differ on their restrictions of undocumented persons from becoming legally licensed to practice.

Beyond all of these challenges, laws that criminalize undocumented immigrants exacerbate the difficulty children face in obtaining an education. Especially after ICE raids, there are drastically lower attendance in schools, declined academic performance, less involvement from parents, the deportation of parents are all effects of the stress that children feel because of the criminalization of immigration.

Statistically, farm workers who have not completed high school are more likely to choose to work in the fields until they are no longer able to. The hope of utilizing education for upward mobility is not likely if they did not complete the 12th grade (NAWS Figure 6.9), but it is still relatively high if they did complete education.

Overall, lack of education for farm worker adults and barriers to accessing education for farm worker children leaves families with little hope for a better life.

Children of Farm Worker Families

Children from farm worker families face their own educational obstacles. Like adults, they too are affected by economic strain. Farm workers have some of the lowest annual family incomes of any U.S. wage and salary workers.

This struggle to make ends meet can leave children with no other option but to work in the fields alongside their parents in order to contribute to the family.

Under U.S. law, children as young as the age of twelve are permitted to work. A report from the Association of Farmworker Opportunity Programs (AFOP) found that farmworker children work in the fields for thirty hours per week on average, often during the school year; while children in other sectors can work no more than three hours per day during the school year. In agriculture there are no limits to how many hours children can work.

In addition to economic pressure, belonging to a farm worker family can often mean moving around often, and this takes an emotional toll on children, which impacts their education. Children of farm worker families also struggle with the separation of their families and lack of job security for both their parents and themselves.