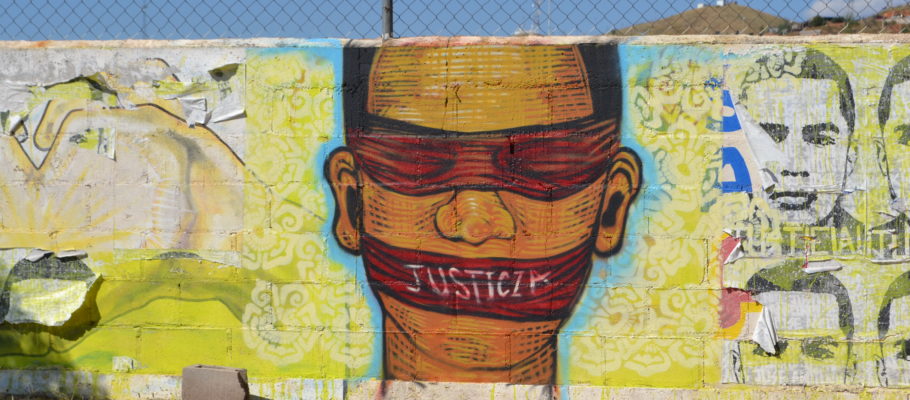

At the corner of International Street in the border town of Nogales, Mexico, a bullet-ridden wall serves as the backdrop to a roadside memorial. The memorial marks the spot where a young boy lost his life at the hands of the Border Patrol.

On October 10, 2012, 16-year-old Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez was shot and killed by a Border Patrol agent for throwing rocks at the border fence. The Border Patrol agent, who shot through a narrow opening in the fence from Nogales, Arizona which towers some 25-30 feet over the city streets of Mexico, emptied all 12 rounds of his .40 caliber pistol and reportedly reloaded in order to continue firing. Dozens of shell casings were found after the shooting and reports state that Jose died with at least 8 gunshots to his back and head.

More than two years later, the family of Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez continues to struggle for justice in the death of their son. Unfortunately, excessive force on the border is not a new issue. Since 2005, more than 46 deaths at the hands of Border Patrol agents remain open with no one being held accountable. And nine, maybe more, lawsuits are pending in cases of death due to excessive force on the border since 2010.

In a recent trip to Nogales, Mexico with The Loretto Community, I stood to pay my respects at the memorial for Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez and was astounded at the overbearing presence of the border wall. I felt so small and helpless in comparison to what my tax dollars had built. High-tech cameras watched our every step as we recounted Jose’s final moments on International Street. I wondered, out loud, what it is going to take to realize we have gone too far; too far from the roots of our shared humanity and too far from the flow of the land that was once without border walls.

The work of the farm worker movement and the struggle for fair, humane immigration reform are intimately intertwined. As I spoke with migrants at Kino Border Initiative later that day, some of whom had just been deported that morning and some of whom were about to begin their journey through the desert, I was reminded at what cost so much of our food is harvested. “The fields…I’d probably work the fields,” said one man when I asked what he would have done for work had he made it through without being deported.

For those of us privileged enough to be able to feed our families, a great responsibility rests on our shoulders to know where our food comes from. No, I am not referring to whether it is organic or local. I am referring to knowing and better understanding the issues for the millions of men, women and children who harvest the fields everyday. We have a responsibility to know how our immigration policies and trade agreements affect the people who make our Thanksgiving tables possible. We have a responsibility to better understand the push and pull factors for those who cross a dangerous desert to labor day in and day out to feed their families back home.

As we await Washington’s post election response to our broken immigration system, I can’t help but wish that those proposing bills would be required to first visit with the people stuck in the middle. It is true we simply cannot know another’s journey until we have walked a mile or two in their shoes. For those with worn soles both in Nogales and in the fields across the United States, I pray that 2015 brings swift and fair reform.

For more information on immigration reform, Operation Streamline, life on the border and the New Sanctuary Movement, please click here.

For more pictures from our recent trip to Nogales, Mexico, please click here.

Rev. Lindsay Andreolli-Comstock

Executive Director