Download: A Timeline of Immigration Policy & Farm Workers

Una cronología de la política de inmigración y campesinos en los EE

Learn even more about immigration and farm workers.

1600s

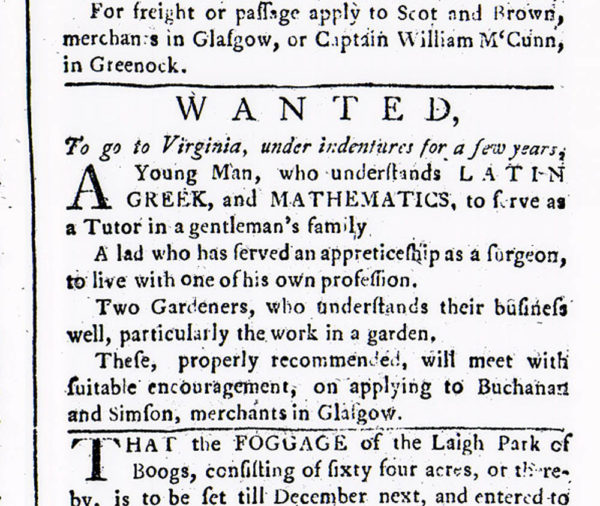

Indentured Servants from Europe, mainly from England, arrived in Virginia as cheap labor to help care for the land in 1607 around when the Thirty Years War depressed the European economy.1 They were guaranteed passage into the colonies in exchange for their labor.

When indentured servants weren’t providing enough labor, Black African people were brought to the U.S. as enslaved persons to work in the fields and as domestic servants. The first Black African enslaved people arrived in Virginia in 1619, and the slave law passed in MA in 1641, and in VA in 1661.2 Due to the power rising among the colonial white elites and landowners and Bacon’s Rebellion (1676-1677), there was a shift from servitude to the rise of slavery.

According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, by 1866, 12.5 million Africans were shipped to the New World,3 and professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. estimates that 388,000 to 450,000 people were shipped to the U.S., which was less than what other countries in the Caribbean and South America received.4

Before the domination of cotton in American agriculture, sugar cane plantation was the dominant labor that required constant work.5 By 1860, it had reached nearly 4 million, with more than half living in the cotton-producing states of the South.6

IMAGE 1 “An advertisement from the newspaper Glasgow Courant, 4 September 1760, for indentured servants to go to Virginia.”https://www.theglasgowstory.com/image/?inum=TGSE00606

Sources:

- “Indentured Servants in The U.S.,” History Detectives, accessed June 8, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/indentured-servants-in-the-us/.

- Ibid.

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “How many Slaves Landed in the U.S.?” The African Americans Many Rivers to Cross, PBS North Carolina, accessed June 8, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/how-many-slaves-landed-in-the-us/.

- Henry Louis Gates, Jr. “ How Many Africans Were Really Taken To The U.S. During The Slave Trade?” America’s Black Holocaust Museum, last modified January 6, 2014, https://www.abhmuseum.org/how-many-africans-were-really-taken-to-the-u-s-during-the-slave-trade/.

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/history-slavery-smithsonian.html Accessed July 31, 2021.

- “Slavery in America,” History.com, accessed June 8, 2021, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/slavery

1846-1848: The Mexican American War

Following the end of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), in which Mexico was defeated, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted America the land of California, Texas, parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Nevada.1 Tens of thousands of Mexicans thus became residents of the U.S.2 After the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, around 1890, Mexicans migrated to the U.S., being recruited by the U.S. railway companies due to labor shortages.3 In many cases, they freely moved across the border for temporary jobs and then returned home.

Sources:

- “Becoming Part of The United States,” Library of Congress, accessed June 8, 2021 https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/mexican/becoming-part-of-the-united-states/

- Ibid.

- “U.S.-Mexico Relations 1810-2010,” Council on Foreign Relations, accessed June 9, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-mexico-relations

1865–1866

The Black Codes are created after the Civil War with the intention of limiting the rights of black people. The laws include required permits for black people who want to work in sectors other than agricultural labor, bans on raising their own crops, and required permission to travel. These laws were repealed in 1866.

The age of post-war Reconstruction begins. Indebted to landowners, formerly enslaved persons and their descendants continue to work in the fields.

The systems of tenant farming and sharecropping emerge. Tenant farmers typically paid landowners for the right to grow crops on a certain piece of property. In addition to having some cash to pay rent, they also generally owned some livestock and tools needed for successful farming.

Sharecroppers, on the other hand, were more impoverished than tenant farmers. With few resources and little or no cash, sharecroppers agree to farm a certain plot of land in exchange for a share of the crops they raise. The amount of crops the sharecropper gave over to the landowner depended on the agreement with the landowner.

Late 1860s–1870s

The Civil War ceased in 1865, and the Reconstruction began. In the years following the Black Codes (yearly labor contracts) were created with the intention of limiting the rights of Black people. The laws required permits for Black people who wanted to work in sectors other than agricultural labor, bans on raising their own crops, and required permission to travel.1

The South re-established this code as “Jim Crow Law”, abolished by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The 13th amendment in 1865, abolished the practice of slavery after over 200 years. The Reconstruction Act by Republican in 1867 called southern states to ratify the 14th amendment (citizenship rights), and in 1870, the 15th amendment granted suffrage to African Americans.

Indebted landowners, formerly enslaved persons and their descendants continue to work in the fields.

Early 1870s, the tenant farming and sharecropping system dominated the south for cotton-planning, leading the sharecroppers to owe more to the landowner. Tenant farmers typically paid landowners for the right to grow crops on a certain piece of property. In addition to having some cash to pay rent, they also normally owned some livestock and tools needed for farming.

Sharecroppers, on the other hand, were more impoverished than tenant farmers. With few resources and little or no cash, sharecroppers agreed to farm a certain plot of land in exchange for a share of the crops they raise. The amount of crops the sharecropper gave over to the landowner depended on the agreement with the landowner.2

Sources:

- “Black Codes,” History.com, modified January 21, 2021, https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/black-codes

- Charles C. Bolton, “Farmers Without Land: The Plight of White Tenant Farmers and Sharecroppers,” Mississippi History Now, modified March 2004, http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us/articles/228/farmers-without-land-the-plight-of-white-tenant-farmers-and-sharecroppers

1860s–1930s

Farming becomes a large-scale industry. The U.S. begins importing Asian labor as African Americans move into other industries and the need for labor increases. By 1886, 7 out of every 8 farm workers in California were Chinese, Japanese and Filipino.1

IMAGE 1: Japanese immigrant farmers and their families excelled in the cultivation and marketing of intertilled fruits and vegetables, which many white farmers resented. Dorothea Lange, Courtesy of Library of Congress. https://americanhistory.si.edu/righting-wrong-japanese-americans-and-world-war-ii/japanese-immigration

Sources:

- “Farmworkers and Immigration,” the NC Farmworker Institute, accessed June 11, 2021 http://www.bienestar-or.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Farmworkers-and-Immigration.pdf

1882

The Chinese Exclusion Act bans the employment of Chinese workers. It is the first major attempt to restrict the flow of workers coming to the U.S.1

Sources:

1890s–mid-1900s

Segregation continued under the Jim Crow laws, which systematized inferior treatment and accommodations for African Americans. Former slaves and their descendants continued to work in the fields: debted to landowners or by sharecropping (working the fields in return for a share of the crop produced in the land).

1914–1929

During World War I, migration to the U.S. from Europe declined, increasing the demand for Mexican labor to fill the void. Growers lobbied to create the first temporary guest worker program for Mexicans, later known as “the First Bracero Program.” The program ended in 1921. During the lifespan of the program, 76,862 Mexican workers were admitted to the United States, of which 34,992 returned to Mexico.1

The U.S. government passed the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 to restrict the flow of European immigrants but excluded Mexicans from the Quota requirements. The immigration Act of 1924 then extended the restrictions to Asian labor migrants, while Mexicans were still admitted with visa fees and taxed from those entering the country. By 1930, the U.S. census counted 600,000 Mexicans residing in the U.S, a 200,000 increase from 1919, comprising less than 5 percent of the immigrant workforce, without counting undocumented immigrants.2

Sources:

- Vernon M. Briggs Jr. “History of Guestworker Programs: Lesson from the Past and the Warnings for the Future,” Center for Immigration Studies, modified March 1, 2004, https://cis.org/Report/History-Guestworker-Programs

- “U.S.-Mexico Relations 1810-2010,” Council on Foreign Relations, accessed June 15th, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-mexico-relations

1930s

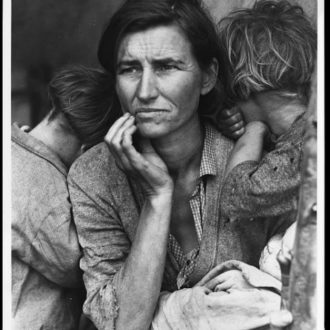

(Migrant Mother). Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection.

The Great Depression and the Dust Bowl (a period of drought that destroyed millions of acres of farmland) forced white farmers to sell their farms and become migrant workers who traveled from farm to farm to pick fruit and other crops at starvation wages.1

Due to the lack of jobs during the Great Depression, more than 500,000 people of Mexican decent were deported or pressured to leave during the Mexican Repatriation, and the number of farm workers of Mexican descent decreased.2 Some estimate that as many as 1.8 million people were deported. Many of the people deported were U.S. citizens. The rational was that the resources and jobs should go to Whites rather than those of Mexican descent.

The U.S. government passed a series of labor laws to protect workers but excluded farm workers and domestic laborers. In 1935 the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) provided the right to organize without retaliation but excluded farm workers and domestic workers.3 The 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) created overtime rules and established the minimum wage, which did not cover seasonal workers.4 The FLSA also failed to include youth farm workers in its standards for youth laborers.

Farm workers were excluded from labor laws in the 1930s, and they are still excluded from most basic labor protections available to workers in other industries. Learn more about farm workers by subscribing to our e-news and watch our video to better understand the continued ramifications of being excluded from most labor protections.

Sources:

- “Dust Bowl” History.com, Last modified August 5th, 2020, https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/dust-bowl#:~:text=the%20Great%20Depression%3F-,Okie%20Migration,traveled%20west%20looking%20for%20wor

- Jasmine Aguirela, “Citizens Facing Deportation Isn’t New. Here’s What Happened When the U.S. Removed Mexican-Americans in the 1930s,” TIME, August 2, 2019, https://time.com/5638586/us-citizens-deportation-raids/

- Kaitlyn Henderson, “Why millions of workers in the US are denied basic protections,” OXFAM, November 20, 2020,

- Ibid.

1942–1964

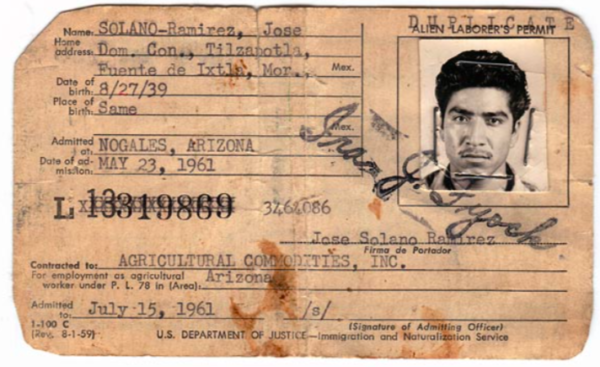

Due to labor shortages during WWII, the U.S. government started the Bracero Program in 1942 (Bracero means “one who works with their arms”). The program imported temporary laborers from Mexico to work in the fields and on railroads. The program was also seen as a complement to efforts against undocumented workers, or programs of deportation (such as Operation Wetback). Enforcement of regulations on Bracero wages, housing and food charges, was negligible. The Bracero Program continued informally and ended in 1964 due to these abuses.

IMAGE 1: Migrant laborer. Washington County Museum’s Exhibit https://www.oregonlive.com/hillsboro/2012/11/washington_county_museum_retri.html

IMAGE 2: Bracero worker ID card for Jose Solano Ramirez, who entered the United States for work in 1961. Smithsonian Institution https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5205763

Sources:

- https://cis.org/Report/History-Guestworker-Programs

- https://www.labor.ucla.edu/what-we-do/research-tools/the-bracero-program/

1943

Sugar cane growers in Florida obtain permission to hire Caribbean workers to cut sugar cane on temporary visas through the British West Indies Program.

Image 1: Jamaican laborers in the field cutting cane by machete in Clewiston, Florida. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/255918

1952

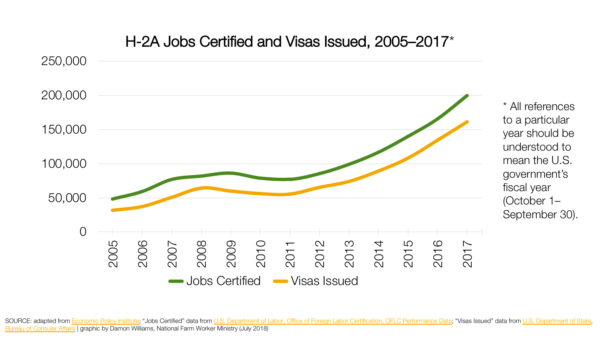

A temporary guest worker H2-A and H2-B visa program was made an official law as part of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) 1

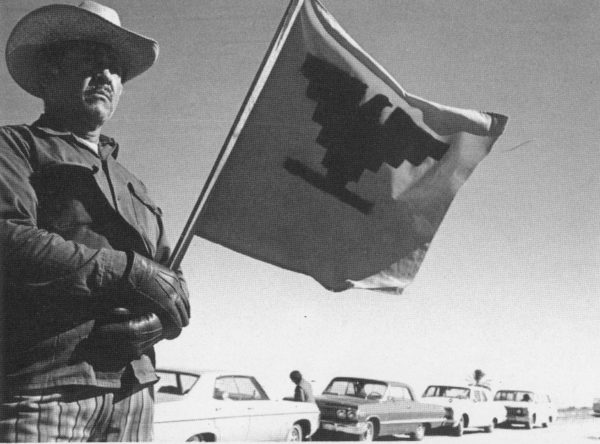

IMAGE 1: UFW protesters. https://disparitytoparity.org/secure-land-tenure-first-step-toward-racial-justice-agricultural-parity/

Sources:

- Vernon M. Briggs Jr. “History of Guestworker Programs: Lesson from the Past and the Warnings for the Future,” Center for Immigration Studies, Last modified March 1, 2004, https://cis.org/Report/History-Guestworker-Programs

1960s–1970s

Post World War II, the African-American agricultural workforce disperses into other industries in search of better opportunities, creating a shortage of labor in the fields. By the 1960’s and ’70’s, the farm labor force is mostly comprised of immigrants, primarily, though not exclusively, from Latin America. Filipino farm workers organize around labor issues on the West Coast, as do Mexican American farm workers.

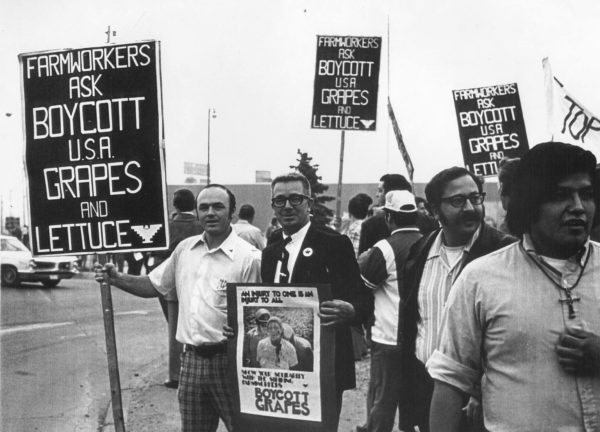

Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta join the organizing efforts of the Filipino farm workers, culminating in the landmark Delano Grape Strike of 1965.

The United Farm Workers (UFW) begins to form. Their worker-led movement draws national attention to farm workers’ struggles, and lays the groundwork for other farm worker unions and organizations, and the modern farm worker movement is born.

Influenced by the Civil Rights movement and by figures such as Mahatma Gandhi with an insistence on nonviolent actions, the organizing on the West Coast inspires many white Americans to join the farm workers. An estimated 17 million Americans support the grape and lettuce boycotts of this period (United Farm Workers).

Another galvanizing moment for many white Americans is the airing of Edward Murrow’s 1960 television documentary, Harvest of Shame, which brings to light the modern-day slavery conditions of American agricultural labor. Available on YouTube: 1960: “Harvest of Shame” – YouTube

1980s

CATA (El Comité de Apoyo a los Trabajadores Agrícolas, The Farm Workers Support Committee) is founded in 1979 as a non-profit organization focused on organizing and empowering the immigrant community as they fight for justice for themselves, their families, and their communities.

The Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) gains traction in the Midwest, Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN) organizes workers in the Northwest, and the Farmworker Association of Florida (FWAF) is established in Central Florida.

The Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act of 1983 passes, requiring employers to disclose occupational expectations and comply with proper documentation in the workplace (such as pay stubs). The act, however, does not guarantee collective bargaining or freedom of association rights.

In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act passes, intending for the increasingly Mexican farm labor population to be able to gain citizenship, thus qualifying them for the U.S. federal minimum wage. In fact, 1.1 million Mexican farm workers gained legal status through IRCA. The situation in the fields changes little, however, and with the late 1980s comes the rise of farm labor contractors (FLCs), who seek undocumented laborers in order to be able to pay them less. As a result, many of the intended beneficiaries seek work in friendlier industries (Migration Policy Institute).

1990s

The farm worker movement continues to grow and the Coalition of Immokalee Workers begins to organize in South Florida in 1993.

Undocumented migrant workers and their families move together from state to state to work the various harvests. They then return to Mexico or stay near the border in the off-season. Despite less-than-ideal treatment by growers and poor working conditions, this system works for many farm worker families.

In 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is established. Between 1994 and 2001, a flood of cheap, subsidized U.S. corn causes the price of the crop to fall as much as 70% in Mexico. Unable to compete with the subsidized imports, over two million small farmers in Mexico lose their livelihoods, and immigration from Mexico into the U.S. increases.

Late 1990s–post-9/11

Following the attacks of 9/11/01, the U.S./Mexico border becomes increasingly militarized.

In 2003, the Department of Justice’s Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) is dissolved and immigration is re-positioned as a national security issue. ICE – Immigration and Customs Enforcement – is established in 2003 under the Department of Homeland Security. Border crossings become more expensive and much more dangerous. As a result, it becomes riskier for migrant workers to travel with their families, with family separation a frequent and tragic result.

2006

The Secure Fence Act mandates the construction of more than 700 miles of double-reinforced fence along the border with Mexico, through the states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. It authorizes increased lighting, vehicle barriers, border checkpoints and requires the installation of more advanced equipment, such as sensors, cameras, satellites, and unmanned aerial vehicles.

The Agricultural Job Opportunities Benefits & Security Act of 2006 is introduced in the U.S. Congress, which would provide agricultural employers with a stable, legal labor force and protect farm workers from exploitative working conditions. Representing compromises after years of negotiations between the United Farm Workers (UFW), major agricultural employers, and key federal legislators, it would create an “earned adjustment” program. This program would allow many undocumented farm workers and agricultural guest workers to obtain temporary immigration status with the possibility of becoming permanent residents, and later citizens, of the U.S. It revises the existing agricultural guest workers program known as the “H-2A temporary foreign agricultural worker program.” The act did not pass.

2013

The bi-partisan Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act is proposed with included input from the UFW.

The bill includes: 1) Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM Act) and 2) Agricultural Job opportunities, Benefits, and Security Act (AgJobs). The act does not pass.

2014

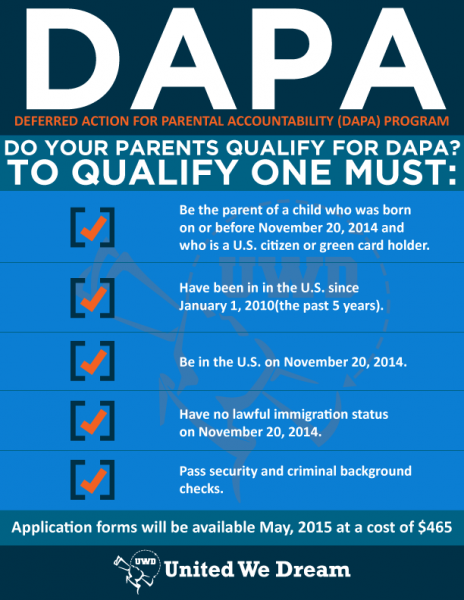

DAPA, or Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, is created by the Obama Administration to allow certain undocumented immigrants who have children who are American citizens to obtain 3-year renewable work permits and exemptions from deportation. This is halted in 2017.

2016

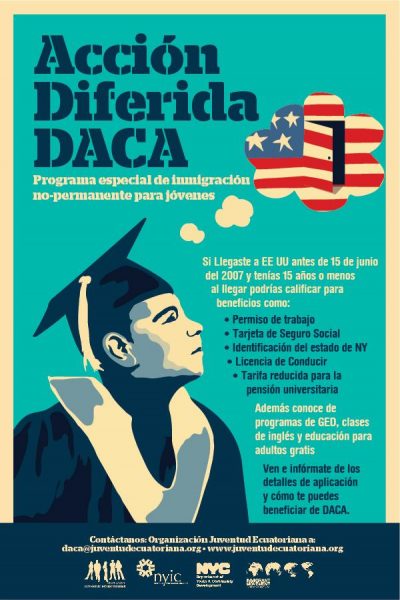

DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, is created by the Obama Administration to allow certain undocumented immigrants who entered the country before their 16th birthday to receive a renewable two-year work permit and exemption from deportation. This is halted in 2017 under the Trump Administration.

Today

Today, most farm workers are immigrants from Latin America, with over 60% undocumented (Southern Poverty Law Center). The vast majority of our nation’s farm workers are from Mexico and Central America, although many African Americans and immigrants from other regions of the world (particularly Asia) continue to work in the fields.

The agricultural industry claims that there is a labor shortage, but farm worker advocates counter that if wages and conditions were acceptable, this shortage would not exist. The perceived shortage has resulted in the exponential growth of the H-2A seasonal worker program. H-2A seasonal guest workers currently provide 8% of annual crop farm labor – up from 2% in the 1990s (Migration Policy Institute). The H-2A program has expanded rapidly from 139,832 jobs in 2015 to around 370,000 in 2022. Learn more about the H-2A program here.