“He had such a clear understanding of servant ministry,” said Pat Hoffman.

“We knew instantly [when we met him] that we would do anything he asked,” said Susan Drake.

“He was very charismatic, very personable,” said Richard Cook.

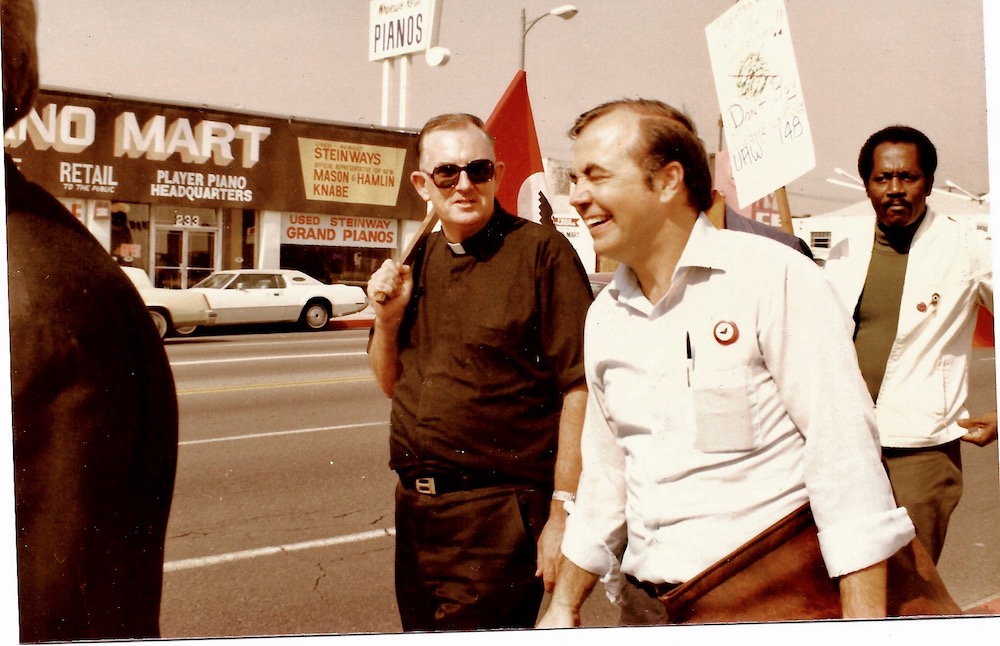

And it goes on and on. The admiration and respect for Reverend Wayne “Chris” Hartmire, the first Executive Director of the National Farm Worker Ministry, is a central theme in the NFWM’s history. Chris can only be described as the heart and soul of this organization. His story is told throughout the pages of this exhibit – in the founding of the national organization, in his commitment to the movement, in his steadfast solidarity with the workers, and in his gentle leadership style. The story of the National Farm Worker Ministry is the story of Chris Hartmire.

Chris attended Union Theological Seminary in New York City. According to the United Farm Workers, he also worked with young people in East Harlem and later went to jail as a 1961 Freedom Rider in the South. Social justice is in his blood. Chris and his wife, Jane “Pudge” Hartmire, had four children: John, Janie Marks, David and Gordon; and eight grandchildren.

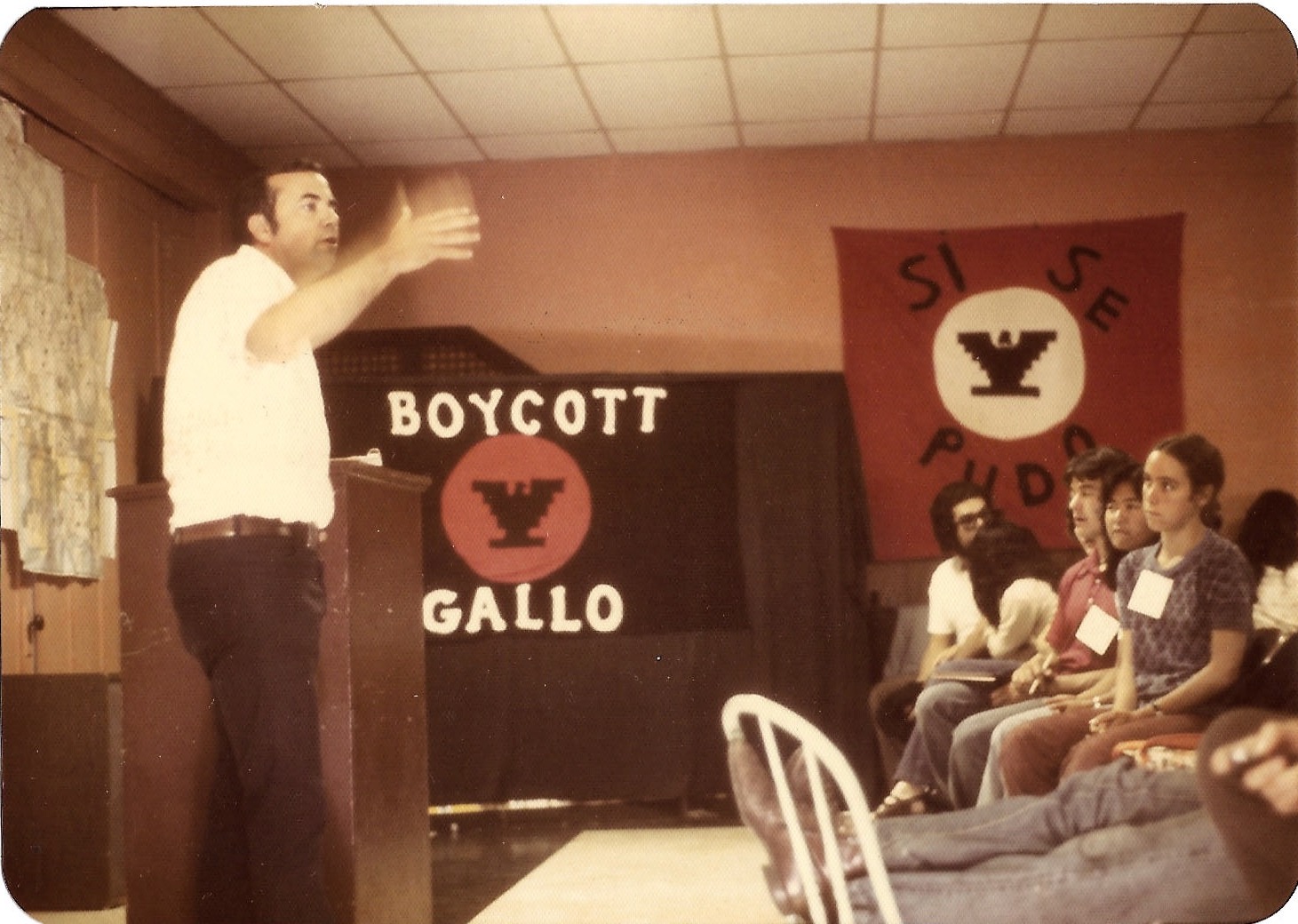

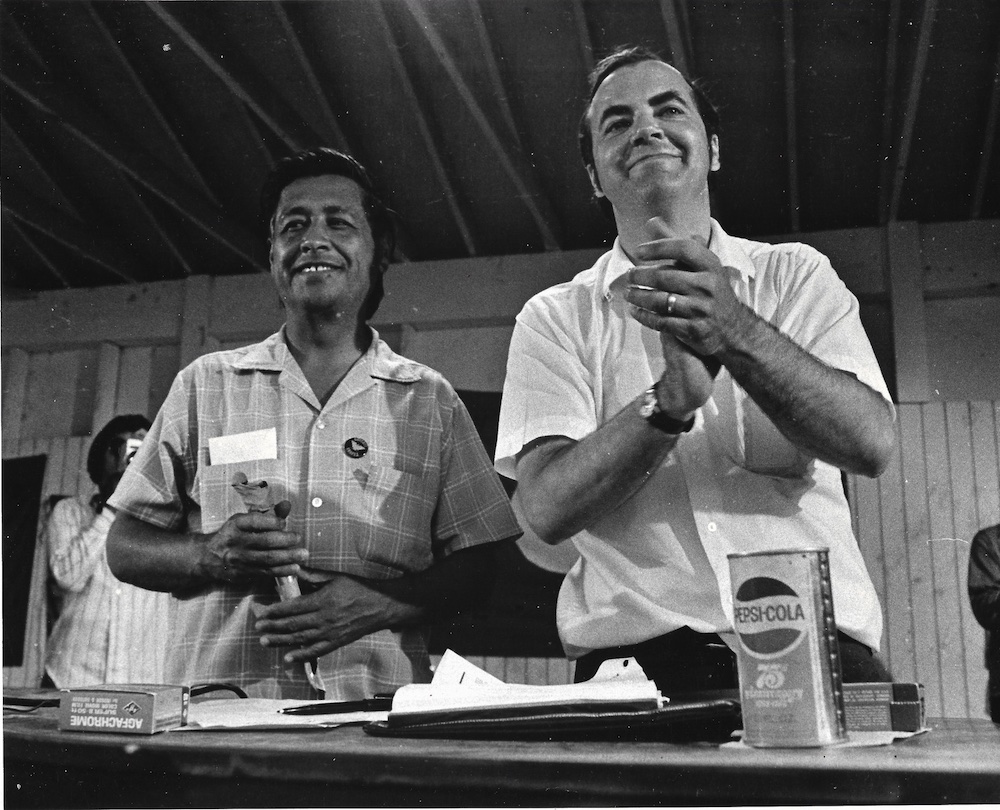

Chris and Pudge moved west in the 1960s when Chris became the leader of the California Migrant Ministry and a close confidant of Cesar Chavez. As the movement grew, so too did the need for organized support from the faith community – and a different kind of support, say those who remember: the farm workers needed advocacy, not charity.

“It was clear that the style of ministry that had been predominating was being ‘kind helpers,’ but Chris understood there needed to be a lot more offered than just helping the poor, which did not change their situation. He was getting his staff trained on community organizing and recognized what a talented organizer Cesar was,” recalls Pat Hoffman when reflecting on the founding of the National Farm Worker Ministry. “He said ‘the Church support network needs to be national or we won’t be able to help them [the farm workers] move into consumer boycotts.’ So that was the movement and the thinking from Chris about why we needed to move from state migrant ministries to a national organization. One thing denominational executives told me was that the thing that kept them going was that they trusted Chris. They knew he would never tell them something that wasn’t true, and they would do what he needed. People of faith and people in churches only get these opportunities once in a while, to support a movement and it’s a privilege. I think the people in the early years really understood that.”

When faith leaders and farm worker organizers met in 1970 to establish a national faith-based organization to support farm workers, Chris was asked to take the lead. While the decision was not without controversy as non-California-based workers had concerns about whether support would expand beyond California, there was general consensus that under Chris’ leadership, a national organization would succeed. “Chris said ‘Cesar has to succeed in California if anyone else is going to succeed,’” recalls Baldemar Valesquez, President of the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC). based in Ohio.

Chris led the NFWM until the early 1980s when he went to work for Cesar Chavez at the UFW. He turned the reins over to his second in command, Fred Eyster. Chris stayed involved in social justice throughout his life and is credited by many with transitioning the faith community from “service to solidarity” – standing alongside the farm workers fighting for human dignity.

“He was extremely clear about servanthood, about using the resources of the church to serve others,” said Gene Boutilier, a founding NFWM board member. “There are ways in which people align themselves with poor people’s movements that retain arrogance and privilege, and Chris worked hard to overcome that with a lot of honesty and integrity. He knew how to bring resources to the table to benefit farm workers and other poor people without egoism. There was integrity. He was the opposite of “we’re here to help you” – he was “we’re in this together and I’m glad to be helpful where I can and learn from you.’”