“I don’t think the ministry is 50 years old. I think it is many more years old,” said Olgha Sierra Sandman, National Farm Worker Ministry original board member. As with all movements, there is no defining the beginning or end. The work started when it was needed and it took a variety of forms over the years. This is the story of the founding of the National Farm Worker Ministry, a continuation of a foundation of work begun many years before, as told by those who were there from the beginning.

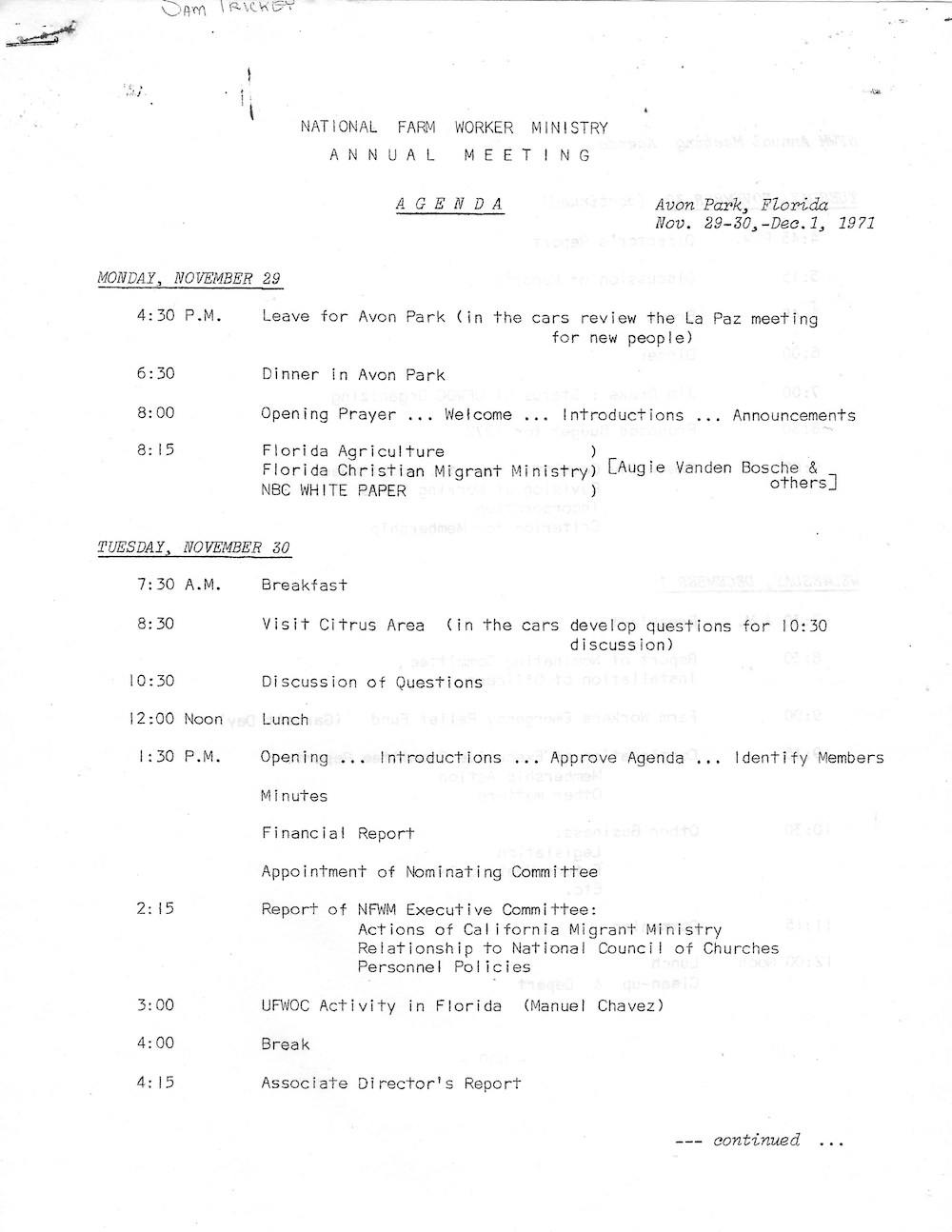

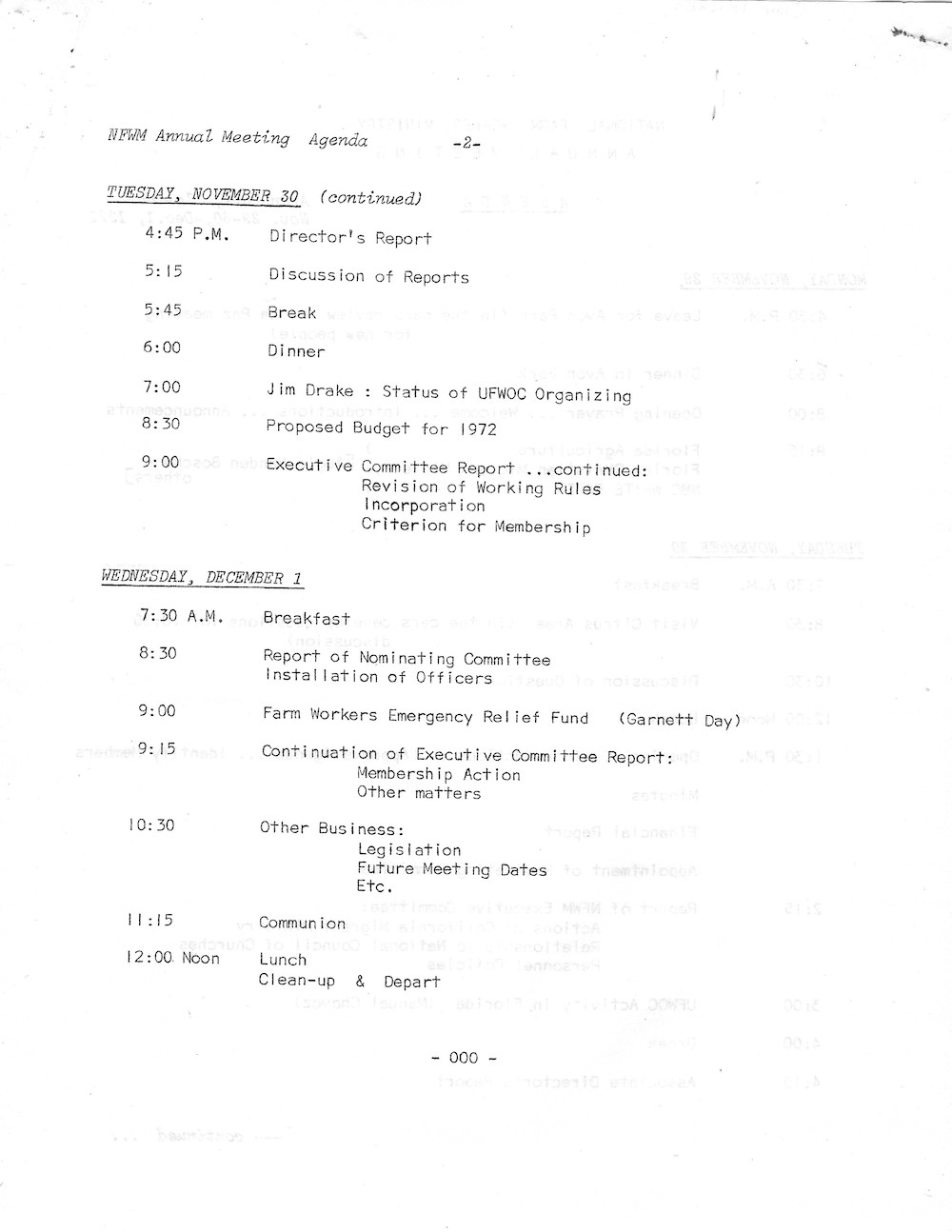

In the early years of the movement, migrant ministries across the country were supporting farm workers who were living and working in horrid conditions for unfair wages. In 1970, leaders of the movement and the faith representatives working in organizing came together in Atlanta to talk about the role of the faith community in the future of the movement. Attendees at these early meetings recall four main areas of discussion in forming the new organization:

- Who would lead it?

- What would it be called?

- What will be the mission?

- Who will be the members?

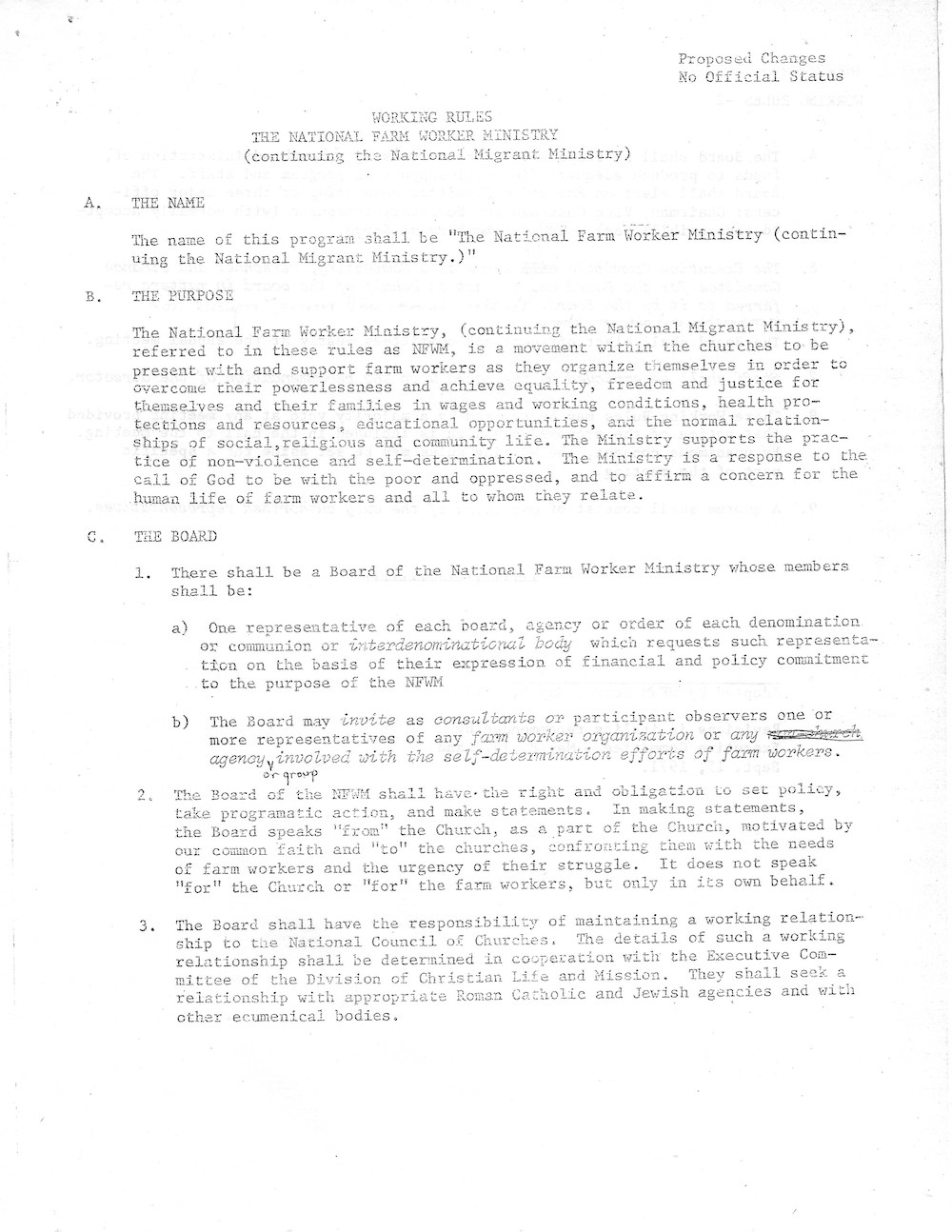

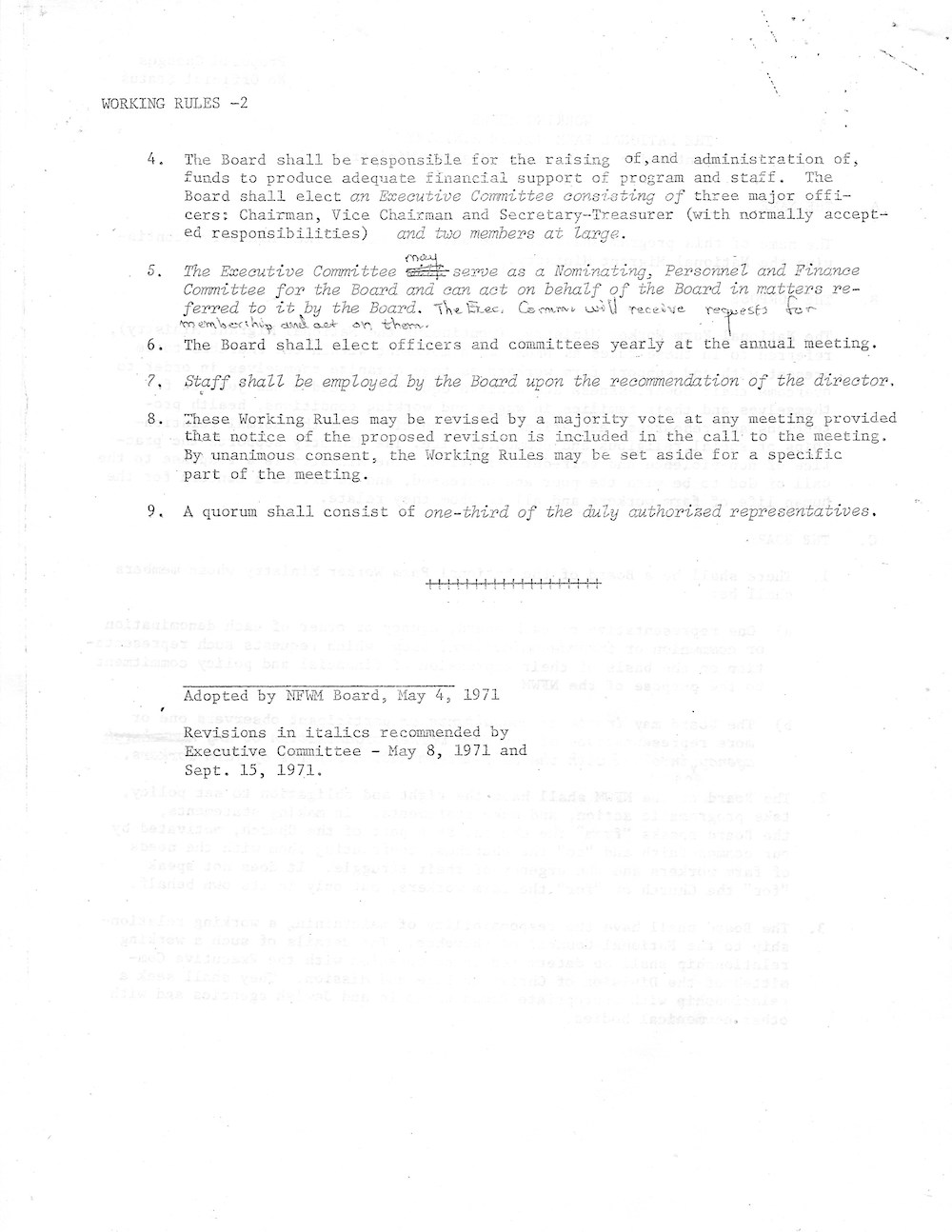

“We needed a structure to match the goal to have a servant ministry,” recalls Pat Hoffman, who worked for both the California Migrant Ministry and then the National Farm Worker Ministry, and authored The Ministry of the Dispossessed.

Olgha recalls that meeting as well: “That was my first contact with what is now the NFWM. I will never forget, Cesar [Chavez] said ‘you know, if you use the word migratory, like national migrant ministry, are you talking about birds who migrate, are you talking about circus people? Who are you talking about? We are farm workers and therefore the most appropriate name for the ministry is National Farm Worker Ministry.’ Nobody argued that. On the contrary, everybody voted that it would be NFWM.”

And so the new name was born. But as the new organization took form, the remaining questions needed answers. All knew the goal was to support farm workers, but the question before the organizers was how?

Baldemar Velasquez, founder of the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC), recalls attending a conference in Texas with other organizers and leaders of the migrant ministries as part of those early conversations: “We were pushing for the ministry to be a support group for farm worker organizing. Some ministers wanted it to be a support service for migrant ministers, but we knew we needed to do something for workers to get better conditions. I was with Gene Boutillier in his hotel until 2AM drafting [the mission] and making sure the ministry was going to be guided to support farm worker organizing.”

The Ministry’s mission is to use its resources and capacity to support the farm workers, says Sam Trickey, a long-time board member who attended the second meeting of the organization: “The claim that they [farm worker organizers] made upon the California Migrant Ministry is that ‘we do not need charity, we need advocacy in the churches’ because that’s where the consumer power is. If, in 1971, I refused to buy red coach lettuce, I am lending my consumer capacity to the farm workers.”

In recounting the history of the organization, many say this is the moment when the faith community shifted from “charity” to “justice.” Others, however, argue that the faith community has always supported justice and advocacy work – it has simply been the strategies and the name that have changed.

Chris Hartmire was chosen to serve as the first Director having previously served as the director of the California Migrant Ministry. “Chris was so dedicated to whatever Cesar [Chavez] needed. He was always working with denominations across the board. He would let them know what we needed. The pace of the work was fast. So many things wouldn’t have happened without him,” Pat recalled.

So the final question to be answered was the composition of the membership of the organizations: should farm workers be members? The decision was made that NFWM would be composed of faith-based organizations that support the work of its farm worker partners. Sam Trickey explains: “We adopted a servant philosophy: to listen to farm workers and then do within our faith traditions what we could do. We are highly connected but not in command by any farm worker organization.”

The initial work supported the first farm worker partner, United Farm Workers (UFW), led by Cesar Chavez. Early organizers recall following a strategy that “if we can’t get it done in California, we won’t get it done anywhere” Velasquez recalls. The NFWM took its first step onto the national stage with its support of FLOC’s Campbell’s Soup boycott in the last 1970s.

Board members were elected at the first meeting at the UFW headquarters in La Paz, according to Olgha, and from that day forward, meetings have been held in locations across the country where their presence was needed.

“The farm worker movement has to stay connected to the faith community,” said Velasquez. “It’s the churches that have helped us get where we are. In 50-plus years of organizing, the cornerstone of having a moral base has been more important or as important as anything else to allow the farm worker movement to survive to this day.”