When Baldemar Valesquez and the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) began to gain traction for its boycott of Campbell’s Soup Company in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Ministry took its first big step out of California and onto the national stage, recalled Valesquez.

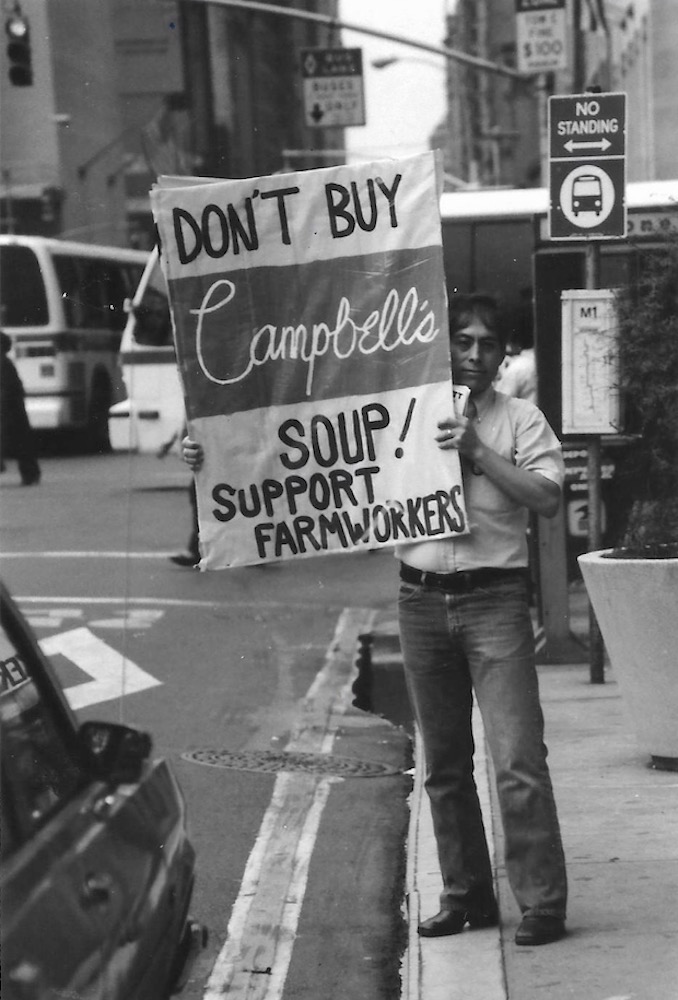

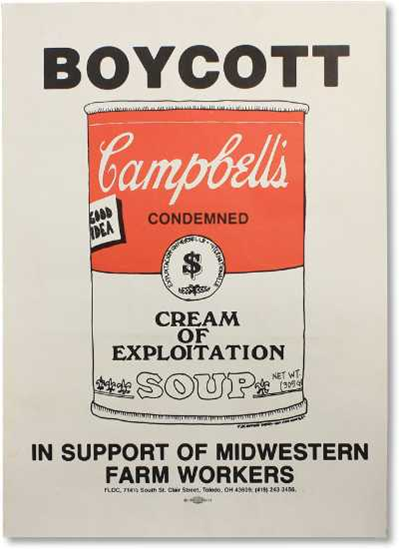

The boycott followed the strike in 1978 of 2,300 workers demanding fair wages through collective bargaining, an end to unsafe pesticide spraying, and improved living conditions, including indoor plumbing and work site toilets. FLOC attempted to negotiate with the Campbell’s Soup Company, but Campbell’s claimed it didn’t directly employ the farm workers and placed all responsibility on the growers. FLOC launched the boycott in 1979.

True to its philosophy to support, not lead, the movement, the Ministry added their voice to FLOC’s fundamentally new supply chain strategy intended to pressure the parent company to increase wages and improve working conditions at the farms from which they purchase produce.

With Ministry staff Sister Pat Drydik and Fred Eyster on the ground arranging training events and the Ministry coordinating regional offices in faith buildings in Chicago, Detroit, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Dallas and Tampa, the boycott gained support throughout the country.

“Sister Pat was central to the organizing of the boycott,” said Valesquez. “Without the Ministry backing the boycott, I’m not sure we would have been successful.”

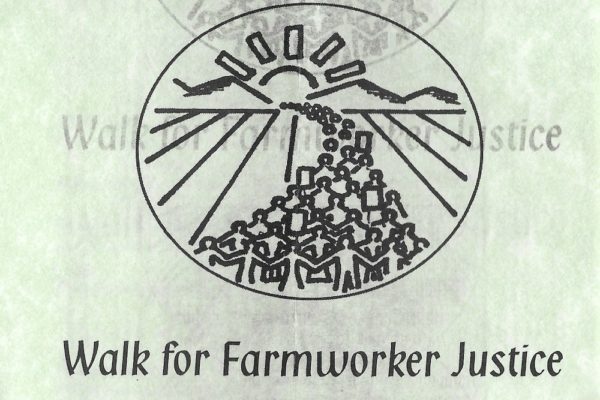

When FLOC undertook the 600 mile March for Justice, a 36 day trek from Toledo, OH to the Campbell’s Soup headquarters in Camden, NJ in 1983, Sister Pat and the Ministry provided essential support: organizing stops along the route, getting permits and clearances, preparing meals, organizing bathroom stops, and coordinating care for the children, all while securing support and commitments from the faith communities along the way. Joy Warren, a member of the NFWM board, recalls hearing a story of Catholic priests in Camden who were asked not to get involved in the event because many of the Campbell Soup executives were practicing Catholics in the city; however, as the marchers made their way into the city, the priests welcomed the farm workers and washed their feet on church steps in an act of support.

According to Virginia Nesmith, former Executive Director of the NFWM, the Ministry also led the national campaign to encourage schools to support the boycott by resisting participation in Campbell’s Soup’s Labels for Education program.

The almost decade long national boycott resulted in the first three way labor contract between farm workers, growers, and a corporation.

The Global Nonviolent Action Database reports that “On February 19, 1986, after two years of scattered negotiations, the FLOC, Campbell’s Soup, and Campbell’s tomato and pickle growers in Ohio and Michigan signed a historic three-way labor contract. Elections were held on farms supplying Campbell’s, and over 3,100 farm workers signed on to join the FLOC. Under the agreement, these workers were guaranteed union recognition and had an equal voice in negotiating their wages and working conditions. In addition, now all workers were clearly classified as paid employees with guaranteed minimum earnings and a system of incentive payments for workers that produced higher yields. Farm workers also now had workers compensation, unemployment compensation, and Social Security benefits. These new agreements guaranteed that farm workers had a direct voice in conditions that could affect their well-being.”